DAME NELLIE MELBA SINGS!

During WW1 the science of wireless telephony – sending and receiving speech instead of Morse code-- had taken huge strides. Based on new developments in thermionic valve technologies, at the Brooklands, Joyce Green and later Biggin Hill research stations, the Royal Flying Corps had developed lightweight reliable telephony equipment capable of over 100 miles’ range, including air to air communication. This technology would soon enable the birth of civilian mass air transport in 1919, with the Writtle based Airborne Wireless Development Department under Peter Eckersley providing the first air traffic control systems, coupled with accurate direction finding based on H.J Round’s work during the First World War.

In early 1919, really as a piece of pure blue sky research, The Marconi Company began a project to research and develop a new range of high power wireless telephony transmitters, pushing the bounds of this new, but still low power technology. The equipment they produced would become known as ‘panel sets’, each capable of transmitting at different output powers, 0.25 kW, 1.5 kW, 3 kW and 6 kW. The Company also started design work on a range of high power valves to meet the requirements of these new transmitter designs. In March 1919, just four months after the end of the First World War, one of the new 3 kW wireless telephony transmitters was installed at the Ballybunion station in Ireland under the direction of Captain Henry Joseph Round.

Captain Henry Joseph Round M.C.

H.J. Round joined the Marconi Company in 1902. A brilliant engineer, during his life long career with the Marconi Company he added much to the science of thermionic valves, made significant developments to ASDIC radio direction finding, and pioneered many other areas of wireless technology. His pioneering work with radio direction finding won him the Military Cross, and resulted in the Battle of Jutland, the largest naval battle of the First World War.

The Ballybunion Station

Despite references in several publications, the Ballybunion Station was not built by Marconi, and never operated commercially. The station was built by the Universal Radio Syndicate, who started construction in 1912. The station had not obtained a commercial licence by the time World War 1 started and the company went into liquidation in 1915. A sister station at Newcastle, New Brunswick, built to the same design as Ballybunion, suffered a similar fate. The Marconi Company bought the two stations from the liquidator in 1918, mainly to prevent their use by potential competitors. The Marconi Company did not use the stations commercially, but found them to be useful and remote research locations, including communication with the R34 Airship in July 1919. The contents of Ballybunion were sold for scrap to a Sheffield based scrap merchant, Thos. W. Ward in 1925.

After the new transmitter was installed in Ballybunion, H.J. Round’s colleague, Marconi engineer W.T. Ditcham began broadcasting a regular daily experimental speech ‘programme’ over 12 days on a wavelength of 3,800 metres using the call sign YXQ. By 1919, Bill Ditcham had accumulated a huge wealth of experience in every aspect of wireless communication. Back in 1906, he had started working for the De Forest Wireless Telegraph Syndicate, and in 1912 had moved to work with Grindell Matthews, who had started to experiment with speech telephony. His ambitious claims and plans for his stations near Letchworth were cut short by the First World War and his Company went bankrupt. After war service, W.T. Ditcham inevitably joined the Marconi Company, and started working alongside H. J Round as his Dr Watson. At this time Ditcham and Round probably knew more about high power radio speech transmission than any other engineers in the world.

Ditcham and Round’s experimental Irish transmissions were all carried out during the hours of daylight between 10.00am and 1.00pm. The principal objective of these tests was to prove that with the combination of the new oscillating valve transmitter and the modern Marconi valve receiver only a small amount of power was required to transmit telephonic or telegraphic messages across the Atlantic. The tests were also designed to provide data on what would be required to develop a commercial telephony operation over such a range. The tests were successful and W.T. Ditcham became the first European voice to cross the Atlantic, where [a] Mr. W.J. Picken was in charge of the receiving apparatus at Louisburg, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. The signal from the station was heard very clearly, via a small frame aerial 6 feet square using a Type 55 Receiver, both at Chelmsford and Louisburg.

The success of this initial experiment in Ireland was to lead to far greater things. In late December 1919 the Marconi Company installed and began testing a 6kW telephony transmitter at its main Chelmsford factory located in New Street. Operating under an experimental Post Office transmission licence, and using the radio call sign MZX, its sole purpose was again to investigate the properties and problems associated with long distance high power speech transmission. The new Chelmsford transmitter fed into a huge 'T' shaped wire aerial that was suspended between two massive, 450ft high masts, set 750 feet apart, known locally as the 'drainpipes'. These huge steel tubes had dominated the Company's New Street works and the town since they were erected in 1919. Five sets of insulated stays connected each mast with four steel anchors set into 100-ton concrete blocks. Normally the new trials would not have raised much comment as the company was always testing new equipment at its Chelmsford sites. But this time something extraordinary occurred, almost by accident.

What happened next was to change the world.

The early days of radio broadcasting were to be dominated by the enthusiasm and continual pressure generated by a growing band of radio amateurs. It seems these pioneers were always listening in, patiently ‘tickling their cat’s whisker’ receivers. A growing number also started to experiment with ever complex arrangements of the new thermionic hard valves. During WW1 a huge number of people had been trained (mainly by the Marconi Company) in the use of wireless equipment, many more had seen it in use on a daily basis. This interest was accelerated after the end of the war as the Government immediately dumped large quantities of ex-surplus electrical, wireless equipment and the new ‘hard’ vacuum valves on to the civilian market.

But in January 1920 the content of the first Chelmsford transmissions left much to be desired. Ditcham and Round simply followed the Company prescribed format standard speech tests for telephony transmission. But weeks of continually repeating railway station names from Bradshaw's train timetable, broken only by the occasional time check, could drive even the most dedicated of company men to distraction. Ditcham’s normal routine was:

‘MZX Calling; MZX calling!

This is the Marconi valve transmitter in Chelmsford, England, testing on a wavelength of two thousand, seven hundred and fifty metres. How are our signals coming in today? Can you hear us clearly?

I will now recite to you my usual collection of British railway stations for test purposes. The Great Northern railway starts at Kings cross, London and the North Western Railway starts from Euston: the Midland railway starts from St Pancras; the Great Western .....Boston to Great Grimsby, New Holland and Hull. Boston departs at two forty-four, six fifty, nine twenty, one forty-five....’

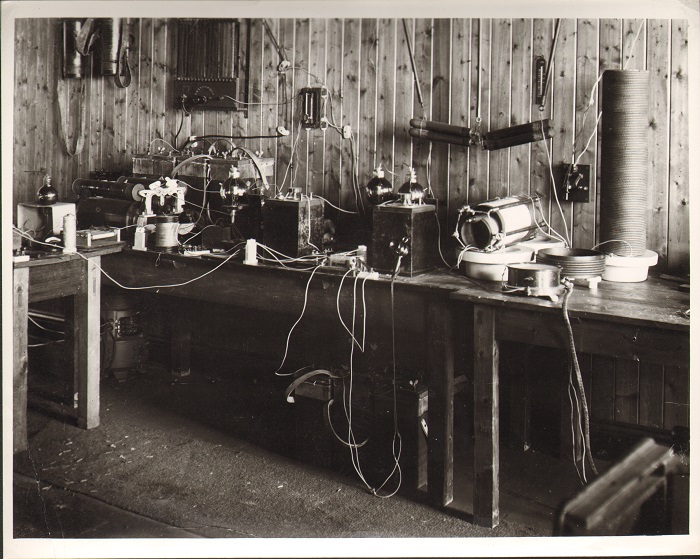

Having tested at length in Ireland, and now repeating themselves in Chelmsford, the Marconi engineers quickly become very bored with normal proceedings. They now decided to do something totally different. On the 15th January 1920 they started the first ever true speech 'broadcasts' in Britain by transmitting a programme of speech and gramophone music from the Marconi Chelmsford works. Included in this was what was to become Ditcham’s regular ‘news service’, all transmitted from the New Street Research Department’s Laboratory.

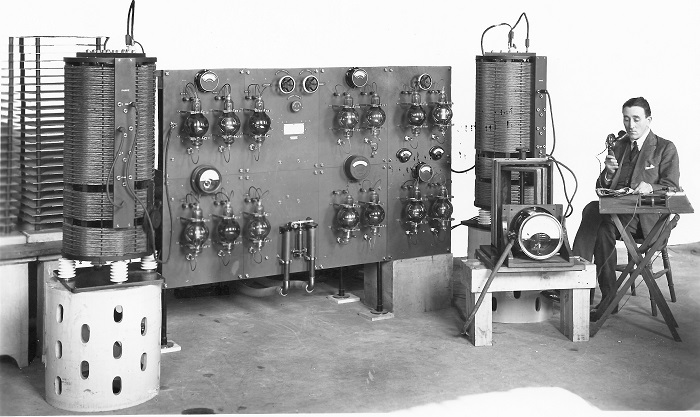

W.T Ditcham and the Melba Transmitter

The famous picture of Ditcham seated by the transmitter in the high power test department. But as with many Marconi publicity photographs of the time the background behind Ditcham and his transmitter was ‘blacked’ or ‘whited’ out, so as not to advertise how basic the engineer’s surroundings really were.

These first, historic and very informal broadcasts could well have gone unnoticed, but two hundred and fourteen appreciative reports soon arrived from amateurs and ship's operators alike who had listened in. The radio amateurs were enraptured to finally hear words and music on their radio sets, and they reported this in glowing terms to the Marconi Company. The Chelmsford station had been heard from Norway to Portugal, with regular reports over 1,000 miles and the greatest reported distance being 1,450 miles. A telegram from Madrid in January 1920 reported exceptional signal strength and quality. The engineering team realised that they had stumbled on something quite extraordinary. It was time to become more ambitious. The 6kW transmitter was quickly replaced with one rated at 15kW input with MT4 and MR4 valves made in the Marconi-Osram works in Hammersmith. Ditcham, Round and another Marconi engineer, Mogridge were all involved with the design work and set about their task with great enthusiasm.

Then, for a brief period from 23rd February until 6th March 1920, their continuing tests became a regular and scheduled series of 30-minute broadcast radio programmes. These were aired twice daily at 11am and 8pm and were designed from the outset to be a regular wireless telephony news service which would take up to 15 minutes, leaving time for three or four short musical items. With W.T. Ditcham as ‘head cook and bottle washer’, organising programmes, announcing news and music items, he was ably supported by the Head of the Marconi Publicity Department, Arthur Burrows and Mr W. Petterigill. Varied staff from the Marconi works were roped in and tasked with organising the short transmissions of musical items. These included Mr G. W. White, (a brilliant pianist), Mr A. V. Beeton on oboe and Mr W Higby on clarinet. Vocalist Mr Edward Cooper from the Marconi works had a good tenor voice and also performed with a local band Freddie and the Funnions run by local business man and entertainer Freddie Munnion. He knew a young soprano, Miss Winifred Sayer, who was in the same group. He suggested she should be invited to take part in the Marconi concerts. Although Miss Sayer was on the clerical staff of the neighbouring factory, Hoffmanns, and so would have to be paid, this idea was approved and a programme of concerts began to be prepared.

Miss Winfred Sayer

The first lady to sing on British Radio. Miss Sayer was announced by W T Ditcham, sitting by the transmitter panel, its valves flashing blue and close to overloading. ‘Hello….MZX calling. This evening for a change we have a vocalist; a lady vocalist too, you'll be glad to know, so I will now ask her to start on her first song. Will you start now, please?’ Nothing could have been more incongruous; the young girl standing on a stone floor strewn with packing cases and nervously holding the 'telephone' to her lips. The first song she sang was an Edwardian ballad called 'Absent'.

Ditcham and Round’s lively series of concerts and news programmes transmitted from the Marconi New Street Works had also not gone unnoticed by the established print media. The newspapers were soon to become very wary of the potential of this new mass communications medium, mainly because it challenged their virtual news monopoly. But it was a newspaper that started the next phase of the story of British broadcasting with the intervention of Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe. Northcliffe was the proprietor of the Daily Mail Newspaper group, and was an influential and successful newspaper owner who founded the Daily Mail in 1896. He had then revolutionized the British press. His format was simple. Keep the stories less than 250 words, and include a murder every day. But it worked. The papers’ content also had to fit into his personal idea of what was newsworthy, but his newspapers reached one in six of every British household, and he had even rescued The Times newspaper in 1908.

It was Lord Northcliffe who now commissioned the first radio broadcast by a recognised professional artiste of international standing. He chose none other than the famous Australian Prima Donna, Dame Nellie Melba. He said that there was ‘only one artist, the world’s very best’...

By 1920, Melba was probably the most famous singer in the world. Between 1904 and 1926 Melba had made almost 200 recordings, and she had triumphed in the opera houses of Europe and America. She had first sung in Covent Garden in 1888 and maintained her position in the golden age of opera for over 25 years, as her voice was remarkable for its even quality over a range of nearly three octaves, and for its pure, silvery timbre. Today her name is also associated with four foods, all of which were created by the French chef Auguste Escoffier. Peach Melba, a dessert, Melba sauce, a sweet purée of raspberries and redcurrant, Melba toast, a crisp dry toast and Melba Garniture, chicken, truffles and mushrooms stuffed into tomatoes with velouté. The current Australian 100 dollar note features the image of her face.

In her lifetime, Dame Nellie Melba achieved international recognition as a soprano, and enjoyed an unrivalled 'super-star' status within Australia, if not the rest of the world. But despite the angelic voice that Nellie Melba was admired for, she was also known for her demanding, temperamental and diva like persona. She was famous for making last minute decisions before a performance, and would often deliberately upstage other sopranos during their performances, grabbing the attention for herself. She felt that three words: ‘I am Melba’, were sufficient to explain her every wish or whim and she tolerated no rivals. So it was this temperamental superstar that Lord Northcliffe wanted to bring to the new wireless audience, but getting the great lady to agree to sing was difficult. Reputedly when she was first approached the singer remained adamant that her voice was not a matter for experimentation by young wireless engineers and their 'magic play boxes'. It took all the persuasive talents that Lord Northcliffe could muster and a huge £1,000 fee, all paid for by the Daily Mail, to get her to agree. Northcliffe had one other advantage. Melba, born on 19th May 1856, was now nearly 64 years old. By the time of the Chelmsford broadcasts she was approaching the end of her career, and the promise of considerable newspaper publicity was something he knew Melba would not refuse.

Lord Northcliffe apart, it was really Arthur Burrows and Tom Clarke who should take the credit for the whole concert idea, and then for making it happen. Burrows was the publicity Manager for the Marconi Company, and Tom Clarke was the News Editor of the Daily Mail and assistant to Northcliffe. Clarke had been a signals officer during the war and had known Burrows from the end of the war, and shared his interest in radio. Ten years earlier, the Daily Mail had promoted and encouraged aviation to its audience of vast numbers of ordinary people. Now its favourite project was radio broadcasting. In 1919 a Daily Mail reporter had roamed Hampstead heath, listening to messages from Chelmsford, while another had travelled by train to the coast with a portable receiver in his suitcase. In May 1920, the Daily Mail included two columns of news ‘collected by wireless telephone’, and soon after a permanent wireless receiving station was installed in the Daily Mail offices. Clarke wrote that ‘these things seemed sheer wizardry in those days’. So Melba had agreed to sing for the wireless and a contract had been signed. But there was just one problem. There was nowhere suitable for her to do it. In 1920 it was totally impractical to move transmitting equipment and aerials to any of the great concert halls of Europe. The great Dame Nellie Melba would have to come to The Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company’s New Street Factory in Chelmsford, Essex. Amazingly she agreed to leave the bright lights of the London stage for one night, and travel to a remote Essex factory. There would be no dressing room, no orchestra, no stage, no lights and in reality, possibly no audience. Or at least not one that the good lady would recognise.

The ‘Australian Nightingale’ was booked to give her now historic thirty-minute radio concert from the Marconi Chelmsford works, on 15th June 1920. But the concert announcement apparently sent the Marconi engineering team into a controlled panic, as they were given very little time to prepare. It was thought that the ‘best place’ in the whole factory for the singer to perform was the first floor, executive directors and senior staff dining rooms at the front of the New Street Works, adjacent to New Street. With mahogany panelled walls, thick carpets and stylish period decor, the rooms were directly accessible from the main works entrance via an impressive main curved staircase. This was considered a ‘fitting’ location for the great lady and would maintain the image of the company. So the Marconi Company’s executive dining rooms were to become this country’s first, professional radio broadcast studio. The engineers’ initial plan was to connect the transmitter, located at one corner of the works through to the new studio at the front of the building. This meant laying in a long, land-line cable right across the New Street works, run it up the outside stairs, down the top floor corridor and into the executive dining room. This would allow the singer to perform in pleasant surroundings, and keep her isolated from all the engineering and the engineers.

A huge amount of effort was also brought to bear on trying to improve the general quality of the microphone and transmitter circuits, but time was short. The cable was duly laid in, but almost at the last moment, during final testing on the day of the concert, it completely burnt out due to the high frequency current induced by test transmissions. The cable apparently actually burnt ‘like a fuse’ up the stairs. These tests also managed to destroy the modulating valves in the transmitter, causing great consternation among the already panic stricken engineering staff. A hurried engineering meeting was called. The engineers were in favour of cancelling the broadcast, but this was considered impossible due to Dame Nellie Melba’s concert schedule. Burrows also pointed out that to cancel now would cause massive damage, both to the reputation of the Marconi Company and to the cause of radio broadcasting in general. So the decision was made to relocate the great lady’s performance to the other side of the Marconi works, actually a disused packing shed, immediately next to the big valve transmitter room. When the great day arrived and despite the valiant efforts of all concerned, the packing-shed was still a gloomy place, its floors and walls bare of any decoration. The building was also still full of innumerable wires and pieces of equipment, although a thick pile carpet had been placed on the floor, almost at the last moment. All the engineers could do now was wait.

On 15th June 1920, Dame Nellie Melba travelled to Chelmsford by train from London, wearing a black dress and a large white hat. At the station she was picked up by a chauffeur driven car and was then taken on a very long tour around Chelmsford, to eventually arrive at the front of the New Street works. On a route advertised beforehand she was greeted by well organised, waving and cheering crowds before arriving at the main entrance, which in reality is just a few hundred metres from the train station. Accompanying Dame Nellie was her son George Armstrong, together with his wife, and two of Melba’s accompanists, Frank St Ledger and Herman Bemberg, one of whose songs she was to perform. The party also included Arthur Burrows, head of the Marconi Company publicity department as her official escort, Marconi Managing Director Godfrey Isaacs and his wife, Lord Northcliffe and his friend and colleague from the wartime propaganda bureau, Sir Stuart Campbell. Dame Nellie Melba was first shown around the works, including the transmitting equipment and the huge antenna masts by Arthur Burrows. Burrows remarked that from the wires at the top her voice would be carried far and wide. Her comment has become a piece of radio folklore: ‘Young man’ she exclaimed, ‘If you think I am going to climb up there you are greatly mistaken.’

It was a testament to Burrow’s amazing vision and determination that every experiment, trial and concert that built the foundations of British broadcasting over the next six years always had Arthur Burrows’ guiding hand behind them. On 15th June 1920 he was there again. It seemed that all was set for the great event, even the transmitter ran up without any problems. Before she could begin singing, Dame Nellie insisted that she must have her favourite pre-concert dinner of partly-cooked chicken, pink champagne and unleavened white bread. This clause, or menu, was specially written into her contract. After her hearty meal in the Directors dining room, Dame Nellie was escorted across the works to the ‘studio’. She passed no immediate comment on the room (to the relief of the engineers who had even try to hurriedly whitewash parts of the walls) and seemed unworried by the Spartan surroundings. Her first glance at the studio floor brought her initial reaction, a firm kick at the new carpet. Dame Nellie announced to the assembled personages of the Marconi Company: ‘First of all we’ll get rid of this thing!’ Dame Nellie was not a woman to be ignored so the new carpet was hastily rolled to one side revealing the bare and un-swept stone warehouse floor. The newly hung curtains also suffered the same fate.

As the concert time approached the engineers were worried. To fail now, with the whole world listening, might well endanger the cause of radio broadcasting for years to come. The newspapers had already proclaimed that: At a quarter past seven this evening a great singer will hail the world by a long trill into space. Thousands of people on land and at sea are eagerly looking forward to hearing the glorious voice of the Australian Nightingale Dame Nellie Melba swelling through space into their instruments.’

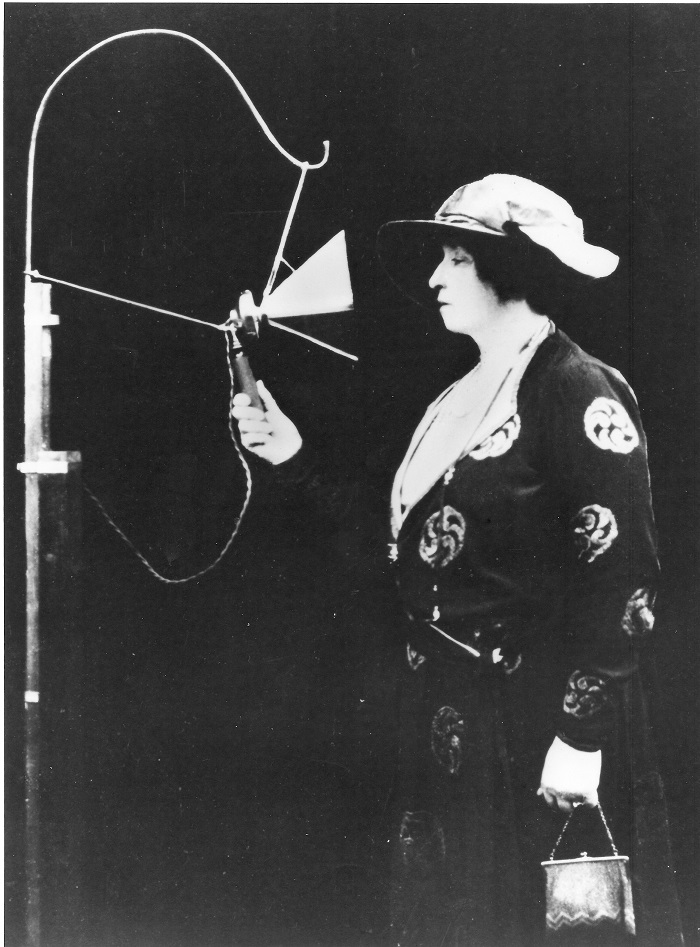

After an interval for photographs and other formalities the programme was arranged to start. The transmitters were run-up, but just as Dame Nellie was about to sing, the last photographer in the transmitter room let off a flash bulb. The engineer on the switch panel saw the reflected flash, panicked and instantly pulled out all the switches, immediately powering down the entire apparatus. While Dame Nellie watched patiently, St Ledger prepared his music, ready to accompany Melba on the piano and the painful process of transmitter warm up had to be gone through again. It was to be only a minor technical hitch. Ditcham was now happy. On a perfect summer evening, it seemed that anybody who could pick up wireless waves throughout the country held their breath as Dame Nellie Melba stood in front of the microphone. Even this was something of a compromise, consisting of a telephone mouthpiece with a ‘home-made’ horn of cigar-box wood fastened to it during the final afternoon’s testing by Marconi engineers, desperate to improve sound quality. The whole contraption was suspended from a modified hat rack by a length of elastic. The microphone and its fragile cone has survived intact to this day; a powerful artefact from the very dawn of radio broadcasting.

Round later remembered that he had great difficulty placing Melba in the makeshift studio, especially as she continually told him that she knew all about it. The distances between microphones, singer, accompanists and the small grand piano were all critical in maintaining as high a quality as possible and Dame Nellie’s position had been marked on the floor. She eventually stood about a yard from the microphone.

A hushed silence fell over the first-ever broadcast studio, and Arthur Burrows announced on air: ‘Hallo, Hallo, Hallo!’ ‘Dame Nellie Melba, the Prima Donna, is going to sing for you, first in English, then Italian, then in French.’ He then apologised for not having control over the ‘atmospherics’. A single chord was struck and at 7.10 p.m. precisely listeners heard their first fleeting notes as Dame Nellie ran up and down the scale. This preliminary sound checks brought a flurry of adjustments in the studio, the engineers swinging condensers and tapping meters.

It was, as the Daily Mail reported, a remarkable scene. Outside the ‘studio’ a large crowd had gathered, but the police requisitioned to keep order were not really required as everyone stood in almost reverential silence. The first lady to broadcast from the Chelmsford site, Miss Winifred Sayer had also been invited. She remembered peeping around the door to watch the amazing scene as it unfolded. Inside the room, a group of VIPs had assembled that included Mr and Mrs Godfrey Isaacs, Mr and Mrs George Armstrong, Lord Northcliffe, Dame Nellie’s son and daughter-in-law and Sir Campbell Stuart. Dame Nellie called her first long silvery trill her ‘hallo to the world’, and the world seemed to be listening. All over the country wireless enthusiasts frantically tickled their cat’s whisker crystal sets, desperately seeking a stronger signal. Headphones were clamped tighter, whole households lapsed into hushed silence. Dame Nellie took a deep breath, and began to sing: A newspaper reported. ‘Punctually at a quarter past seven’. ‘The words of 'Home Sweet Home' swam into the receivers. Those who heard might have been members of the audience at the Albert hall’. This rendition was followed by Hermann Bemberg's 'Nymphes et Sylvains' (in French), Puccini's 'Addio' from 'La Boheme’ (in Italian), and Bemberg's 'Chant Venitien'. Mr. Frank St Leger played the first two songs in the programme and Bemberg, the French Composer, played the third.

Dame Nellie Melba Sings at Chelmsford, June 15th 1920.

The first professional artiste on British Radio. The Marconi Company was embarrassed about the Spartan surroundings that Melba had to sing in. All images of the concert had the background blacked out – if anyone has seen one showing the original room please contact the author!

The Location of Melba’s Studio. Marconi’s New Street Works. 1920.

History was being made from a disused packing shed in the middle of a huge factory. However, as Captain Round later recalled, the transmitter that had initially behaved very well during the concert, started to play up at the start of Melba’s third song. Listening in anxiously on a wavemeter in the equipment room, H.J. Round watched in horror as mid-way through the rendition, one of the transmitter valves started to fail. Then Chelmsford went off air. Shouting instructions for the valve to be changed, he immediately rushed from the transmitter room to the shed where Melba was singing and waited for her to finish the last song. The repair had not taken long, but as far as the world was concerned the concert had abruptly ceased and her third song had been almost completely lost. Thinking quickly on his feet Captain Round called out: ‘Madame Melba, the world is calling for more’. Dame Nellie Melba replied: ‘Are they? Shall I go on singing?’

This was exactly what Round had hoped for, but whereas he had expected just one more song to make up for the partially lost one, in fact the good lady sang four more. While Round was ‘pleading’ for another song, W.T. Ditcham had corrected the fault and a minute or two later the notes of a piano again floated into listeners’ front rooms. After a brief pause for further adjustments to the transmitter, Dame Nellie gave a further encore, repeated ‘Nymphes et Sylvains’, and then sang the first stanza of ‘God Save the King’. It was over. They had done it. Without further fanfare, Burrows stepped to the microphone and simply said: - ‘Hallo, Hallo, We hope you have enjoyed hearing Melba sing, Good Night!’

The wireless sets of the nation, indeed the world then lapsed into silence. The concert was over. The great lady had sung her considerable heart out and the assembled audience both inside and outside the studio spontaneously applauded. It was now up to the engineers to have relayed this to the audience with the clarity it deserved and hope that the partial failure had been compensated for by the extra songs. They knew that the audience was potentially huge and liable to be very critical, indeed nearly 600 new licences had been issued in the two months leading up to the broadcast.

Within days the Marconi Company was to receive its answer as enthusiastic letters from the four corners of the world poured into the Chelmsford office. Radio amateurs and ships’ operators alike reported how they had listened in and sung along. Every commercial station in the world had tuned in and the concert had been received with surprising clarity, and it was voted a great success. The amateur radio enthusiasts even amused themselves during the concert by listening in to the wireless station operators at the new Civilian air traffic control radio stations at Lymphe and Croydon discussing the performance between the songs.

Miss Sayer, the first Chelmsford concert artist, remembered the broadcast and had been personally invited by the Marconi engineers. Actually Winfred went home a little disillusioned. She had heard Melba, but not with the added magic of hearing her via a radio. She was not even introduced to Melba who simply swept by her, Winifred remembered that she was ‘a most peculiar looking woman’. For everyone else it had been a night of success.

Burrows and Clarke had successfully organised an historic event. Round had saved the programme, but regretted not being able to actually hear the concert. Ditcham’s transmitter had behaved well, if not perfectly, and his engineering team had made it all happen. For Isaacs his company had scored a huge publicity coup at no real cost. Lord Northcliffe’s paper carried the story for the rest of the week. The radio amateurs had listened into their first quality broadcast and Melba had made history. Dame Nellie Melba’s historic ‘Hallo to the World’ had been heard with surprising clarity on every kind of wireless set imaginable. A large proportion of the 400 or so immediate replies that the Marconi Company received were from listeners using nothing more than a simple crystal set. These included excellent reports from several Welsh listeners, but the record went to Mr. P.S. Smith on board the SS. Baltic at a distance of 1,506 miles, again using nothing more than a ‘cats’ whisker’ crystal wireless set. The concert had been a resounding success, Dame Nellie's voice had spanned the world and produced excellent signal reports from Sultanabad in Northern Persia, and from Madrid and Berlin in Europe. It even appeared that the popularity of these experimental wireless stations had mollified the somewhat reticent attitude of the Marconi Company toward the possibilities of using wireless telephony for entertainment purposes.

You would expect that British radio broadcasting would explode into life from these experiments during the first part of 1920. More concerts followed from famed Danish Tenor Lauritz Melchior and Dame Clara Butt, who both sang from the Chelmsford New Street works.

Despite the fact that entertainment broadcasting was rapidly gaining favour with the general public, on 23rd November 1920 the Postmaster General spoke to the House of Commons. He announced that the experimental broadcasts from the Marconi Chelmsford Works were to be suspended on the grounds of ‘interference with legitimate services’ and for the time being no more trials would be permitted. Each experimental music programme from the Chelmsford, New Street site had to operate under a special Post Office permit, and there were to be no more permits. In reality there was also a political element to the closedown demand, as the Post Office was already seriously worried about its long held ‘communications monopoly’ in the British Isles.

But it would be another two years before British Broadcasting would come to pass. It would need the talents of the irrepressible Peter Eckersley (who started this story), working in a small hut in a partially flooded field on the edge of the village of Writtle and a new call sign – ‘2MT’ or Two –Emma –Toc.

But that, is, as they say, a whole new story. (Probably best told in 2022?)