Henry Joseph Round was a great man.

His 85-year life was packed with achievement and adventure, crammed full of invention and creation.

Described in one publication as having 'shaped the course of British history' and another as being the 'father of British broadcasting', he was awarded the Military Cross in the First World War and the coveted Armstrong gold medal from the Radio Club of America in 1952.

His determination to progress the world of electronics and radio further and further into the unknown was relentless and astonishing, resulting in the registering of 117 patents during his career.

He has been described as the 'unrecognised' pioneer and, while it is true he didn't receive any civil honour like a knighthood or make front page headlines with celebrity status, he was recognised as a genius within the electronics field and, if you dig deep enough, one can find plenty about him on the invention that would have excited him beyond belief - the internet, the world wide web.

Whether working in London or Chelmsford as Guglielmo Marconi's personal assistant and chief engineer; constructing radio stations in the upper reaches of the Amazon river; working with the Americans in New York or earning a secret name - Captain X - among the shadows of British Intelligence, Henry Round was constantly pushing boundaries in the world of radio and broadcasting.

Even with this insatiable desire to invent, he was a caring and generous family man, devoted to his seven children and numerous grandchildren.

Before returning to look at his professional life, it is important to note that the balance he achieved between work and family meant he was very much loved as father and grandfather.

As far as his work is concerned, his family are immensely proud of this brilliant man - a pride that constantly rises as more is discovered about his life.

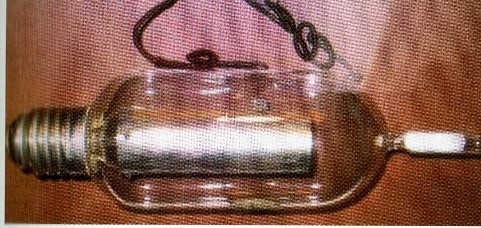

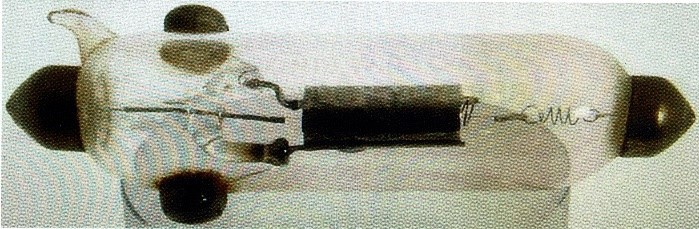

To fully understand the work of Henry Round requires a deep dive into a world of thermionic valves, triodes, oxide coated filaments, anodes, wireless telephony, amplitude control modulation systems, receivers, transmitters, magneto-strictive devices, nickel transducers, oscilloscopes and a host of other devices and processes in a lexicon unintelligible to most people.

Maybe his own understanding about how complex was this work is demonstrated in a quote from Round's acceptance speech when receiving the Armstrong Medal. Talking technically about valves, he made the aside: "or what my wife calls them, bottles.'

Talking, or reading, technology - Round's natural language - is best followed in more academic documents than this one but there are key episodes in his professional life that must be highlighted.

- In 1912, when just 29, he was delegated to lead a team on a hazardous task in Brazil to improve the quality of vital transmissions from two radio stations on the upper reaches of the Amazon. It was an incredibly difficult task with serious obstacles in such a mosquito-ridden environment but he succeeded in his mission to everyone's satisfaction, proving himself again an engineer of resource and unusual ability.

- During the First World War, Henry Round became known as ‘Captain X’ in British Military Intelligence. He installed electronic direction finding equipment in stations across the entire western front and the British Isles. On May 30 1916 his equipment revealed movements in the German fleet off Wilhelmshaven in the North Sea. The British fleet set sail to intercept them and the momentous Battle of Jutland took place which put paid to any further attempts by the enemy to gain supremacy of the oceans. Round’s crucial role in this was revealed in 1920 by Admiral. Jackson, First Sea Lord at the time of the battle, and he was awarded the prestigious Military Cross.

- During the Second World War he worked for the Admiralty on developing sonar to discover and track the movements of enemy submarines. He remained working on echo sounding with Government until 1950.

- In 1952 he was awarded the prized Armstrong Gold Medal by the Radio Club of America ‘in recognition of his contributions during half a century to the radio art, and especially of his revolutionary developments during World War 1 in the fields of direction and position finding and the high amplification of short-wave signals.' A sad postscript is that E.H Armstrong took his own life in 1954 and a letter from Round to the RI of America ended: "I salute the spirit of my great friend."

In between the wars he was prolific in his work, focussing much of his time on valve and microphone development.

Between 1921 - 31 he was chief of Marconi Research and was involved in the famous wireless broadcast of singer Dame Nellie Melba in 1920 and, in 1924, his Marconi-Sykes magneto phone (microphone) facilitated the first outside broadcast of a songbird, a nightingale singing as cellist Beatrice Harrison played nearby.

He developed valve after valve; he directed the installation of wireless transmitters; he produced a gramophone recording system and designed a large audience public address system which was used to relay King George V's speech at the Wembley Exhibitions and he registered patents on synchronising sound with pictures on cinema films.

And so, he continued his work as a persistent inventor and creator.