Now the centenary of the BBC has all but passed – and I think it is fair to say with something of an underwhelming whimper – many ideas were pitched and rejected and as one BBC producer remarked, the BBC had many things it doesn’t want to look back on.

Recent research by David Prosser at the University of Bristol has challenged the traditional historians’ view of the formation of the British Broadcasting Company in the summer of 1922.

It is accepted that the success of the experimental Dame Nellie Melba’s radio concert in June 1920 (and subsequent concerts from Lauritz Melchior and Dame Clara Butt from the Marconi New Street Works in Chelmsford) was followed by a large radio amateur’s protest at that station’s closedown. This led to the formation in February 1922 of Britain’s first scheduled radio station, call sign 2MT, operated from the village of Writtle in Essex by Captain Peter Eckersley. His success, and the rapidly growing popularity of the station led to the request from up to 50 companies to establish their own broadcast stations across the country.

It’s a great story. There are even several most excellent books about it all.

The prevailing view has always been that at this point in mid-1922, for reasons of ‘administrative ease’ and to avoid the ‘chaos’ across the Atlantic, the Postmaster General ‘solved the problems of radio interference by persuading rival manufacturers to invest jointly in one small and initially speculative broadcasting station’. It was then left to John Reith, the BBC’s first General Manager who took up his post in January 1923, supported by Peter Eckersley as Chief Engineer, to build the company and develop the notion of public service radio broadcasting in Britain.

It is now clear that the idea for a single broadcaster, operating across Britain, came not from the Postmaster General, but from the Marconi Company. On 18th May 1922, thirty-nine members of the wireless trade were invited to a key meeting at the GPO’s headquarters near St. Paul’s in London. They were all keenly aware that the future of a new industry rested on their shoulders and that failure might mean, as one participant noted, this ‘whole delightful enterprise which fascinates everybody and which promises good business, will end in a fizzle and disappointment’.

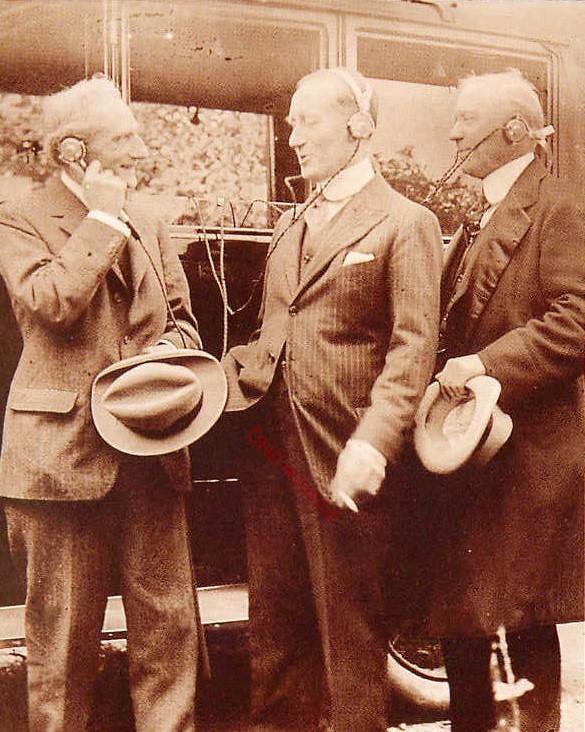

Marconi with Isaacs

This meeting is one of the most significant events in the history of British broadcasting and took place behind closed doors. Although the meeting was chaired by Sir Evelyn Murray, the Secretary of the Post Office, it is Godfrey Isaacs, the Managing Director of the Marconi Company, who emerges from the pages of the meetings transcript as the dominant force in the room. At Isaacs’ suggestion, twenty companies indicated at the outset ‘a desire to have licences’. With broadcasting to be allowed in only eight cities, the technical challenges were evident and the meeting had a lengthy discussion regarding mutual interference, transmitter powers and how slots might be divided between the different broadcasting companies (with their times registered at the Post Office) and operated. The Post Office was always prepared to issue multiple licences, including suggesting that London could be served by up to four different stations on the outskirts, with the Marconi station, 2LO, in the centre. Eventually, Isaacs drew their attention to the ‘commercial aspects of this question, which may possibly lead to a much easier solution of the technical side’. He also suggested after the initial outlay it will cost not less than £50 per day to run each station. Isaac’s then proposed that the new broadcasting stations should be run under just one management so that they could be properly coordinated, ensuring that there would not be more stations than were necessary, and that they would be most economically and efficiently operated. His idea was that ‘a separate entity’ in which all who have licences shall be invested, should run all the stations and should also appoint the management for those stations.

Isaacs further suggested that firms taking part should commit to the scheme for a period of two or three years. Welcoming the proposal, Murray indicated the arms-length approach the Post Office intended to adopt over British radio broadcasting: ‘I do not commit myself to detail and I do not know that it is our business to concern ourselves with those details’. The advantages for Marconi’s competitors were clear and in the next few exchanges the foundations of British broadcasting were laid. Hugo Hirst, the Chairman of the General Electric Company agreed with Isaacs, stating that he would have made a similar suggestion ‘merely from the business man’s point of view’.

Only Metropolitan Vickers the Manchester-based company formed out of British Westinghouse and still associated with its American former owner, resisted the idea of a single provider and called for competition to maintain ‘the best type of programme, the best type of music’, otherwise standards might slip after a time. Isaacs made clear that he didn’t believe a ‘transmitting station can be erected to work efficiently’ without using Marconi patented technology, which he would only make available to a single scheme, thereby ending the debate.

Isaacs and Marconi

It is now clear that both British politicians and the public were fed exaggerated fears of ‘chaos’ on American airwaves in the spring of 1922 in order to restrict transmitter licences to ‘bona fide’ manufacturers, to the exclusion of other potential applicants. New research shows that the Post Office also actively disseminated misleading information about the development of commercial broadcasting in America, either purposely or unwittingly, and in doing so cemented the case for both public funding and a ban on advertising.

Even so, the Post Office entered the 18th May 1922 meeting prepared to licence several manufacturers, under some pressure from Metropolitan Vickers, (who had started testing their own station 2ZY the previous day), and others. But what emerged was a single broadcaster operating at arms-length from the Post Office, providing a ‘public service’ with national content shared between regional stations, funded by a licence fee with advertising prohibited. This is the exact moment the BBC was conceived and these plans for ‘public service broadcasting’ predate Reith’s arrival by at least six months.

It was not the Post Office that proposed the BBC. It was Godfrey Isaacs, Managing Director of the Marconi’s Wireless Telegraph Company, Limited. The man who made the BBC.

Post Script

And working with Allan Pamphilon I was pleased last year that we managed to get Godfrey Isaacs a Blue Plaque now affixed to the New Street works.