Having spent two years completing my National Service in the RAF as a Radar lecturer, I joined Marconi in 1953, a few days after my 21st birthday. I had been recruited to work on Radar but on arrival was given the opportunity to switch to Television. The BBC had restarted a London only service in 1946 with one channel but were expanding. I knew nothing about Television technology, but I had known nothing about Radar Technology when entering the RAF, so it seemed a good opportunity to join a fledgling industry. I immediately went to work for Joe Swain in TV Test. It proved to be a very good decision.

TV Test

TV Test was a very busy department with all the different equipment necessary to produce TV pictures being tested. The transmitters were tested in a different department.

One story from that period concerned acceptance tests for a camera that had been sold to Russia. Mr C. from the Russian embassy arrived to do acceptance tests. He was friendly and talkative and obviously a very proud Russian. In the final camera test area, we had a microphone used as part of our check on the camera intercom system.

Towards the end of his visit Mr. C spotted the microphone and went berserk. He grabbed the mic and demanded to know what it was for. Nothing that we could say pacified him, he was white with fright and anger. He left early that day and barely spoke for the remainder of his visit.

The Television Act was passed in 1954 allowing commercial TV to start in the UK. Four companies were soon authorised to start TV services in London, Birmingham and Manchester, and they all needed both equipment and engineers to get started. The workload in TV Test increased considerably and we were getting attractive offers to join the ITV companies. Several accepted, but I had become fascinated with the technology, particularly the cameras, and my interest was to eventually move to R & D.

Once we had provided enough equipment to get the ITV companies on the air in 1955, I was allowed to move to TV R & D in Great Baddow.

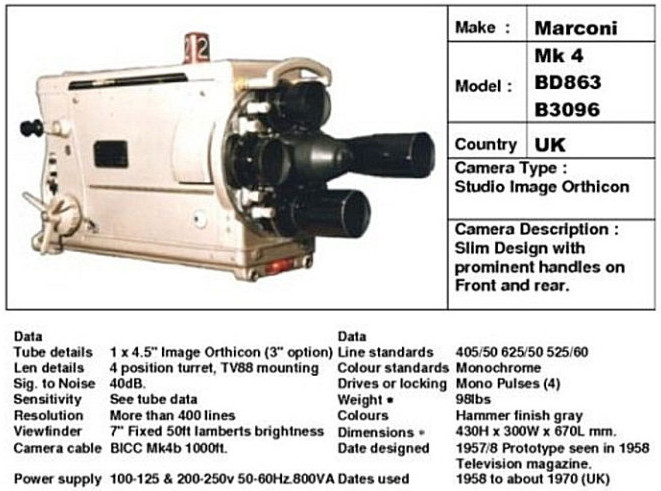

|

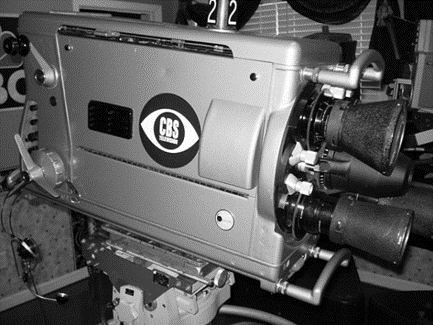

| A MK IV camera sold to CBS |

Frank Grierson, one of the engineers who left to join Granada TV, had digs in the same house as me, and when he left, he gave me his TV set. It was a late1930’s home made set built from a simple design from a pre-war wireless world magazine. It had a very small 9” cathode Ray Tube, assembled in a wooden cabinet 30” X 30” X 30”. The receiver was designed to work with the TRF double sideband signal of pre-WWII experimental TV. However, when TV restarted after WWII a vestigial sideband signal was used. A metal chassis in the base of the cabinet housed all the components, very large and outdated valves. This old set was very unstable, but it did produce pictures and we used it when we were first married. All the adjustments were underneath the chassis and needed frequent adjustment. This involved turning this heavy set on it side, and after doing this a number of times I left it on its side and my wife and I turned our heads sideways to watch! It was a major talking point when we had guests.

TV R & D

The TV Camera electronics team consisted of George Cooper, a very good electronics designer, Dion Edwards and me. The Mechanical designer in the Camera design team, Goeff King, designed a brilliantly simple mechanism for changing the camera lens turret saving space and weight. On his activities outside work he became heavily committed to achieve an optimal quality sound system in his home, and acquired two large concrete sewer pipe sections for his loudspeakers!

His attention subsequently changed when he became a Jehova Witness and this quickly became his obsession. Given an opportunity he would lecture us on the subject. This was harmless and had a useful by product. Whenever JW’s called at home, we could say we talk regularly to Goeff King and they immediately left thinking we were already converts!

Ampex

My time as the Marconi representative at Ampex was fascinating as in many ways Ampex were the exact opposite of Marconi. A small team in the early 1950s produced high quality data and audio recorders. Their breakthrough came when solving the holy grail of television at the time, instant recording and playback of professional quality TV video and audio. The 6 original employees, who had taken their salaries in stock (no values when the cash ran out), became overnight multimillionaires. This included the Janitor who enjoyed working for them and who stayed on as a janitor and amongst other tasks would wash my car for me every month, and get it serviced regularly!

A Can-Do attitude, “anything is possible”, existed through all levels of the company. On one occasion, I received a phone call in the office just before leaving for home, from an Ampex salesman in Pennsylvania, almost 3,000 miles away the other side of the USA and 3 hours ahead of California’s time zone. He was at Brandywine Raceway with the owner and wanted a camera demonstration at a race meeting to clinch the deal. He needed the demonstration the next day at the last race meeting of the season. It seemed impossible, but I checked with the transport department and within an hour they had booked space on an aircraft from San Francisco to Philadelphia for the camera and associated equipment with a seat on the aircraft for me. The aircraft would arrive a few hours before the races started. The transport department then collected the camera and all the associated equipment needed and packed it with a promise to get it on the aircraft.

The next day the salesman met the flight with a station wagon, we loaded the equipment and arrived at the raceway with an hour before the first race. It then transpired they wanted the camera on the roof of the grandstand overlooking the finishing line and access was not much better than a ladder. There was power up there for a water cooler. We carried everything up on the roof and switched on just minutes before the first race started. Although the light level was low, we had excellent pictures. The trotting races with high stepping ponies pulling a lightweight carriage with the jockey sitting at almost ground level were spectacular. The first race was exciting with a very close finish, but just before they got to the finishing post the picture on the monitor disappeared. I checked everything without finding a fault, but the same thing happened in the second race. This time I had monitored the power into the camera and found the voltage dropped from 120 volts down to 75 volts when the photo finish lights switched on, they were on the same circuit!! This voltage was way below the specification.

The raceway staff managed to get the water cooler power onto a more reliable connection and the remaining races were shown complete to the finish. The demonstration was a success, and the salesman got his order.

On another occasion we had a visit from Scientists from the Naval Airbase at nearby Alameda. They had a serious problem losing too many pilots and aircraft in training when landing on aircraft carriers at sea. Their existing film recording system captured each landing on film which was processed overnight for briefings the next day. At the briefing, pilots could not recall last minute adjustments of their landing and believed they were being shown another pilot’s landing. They had no confidence in the existing system.

|

| A crash landing |

The scientists invited us to propose a solution. A small team was quickly formed with Alameda participation and a potential design was ready within two weeks. Two cameras would be placed below the deck on gyroscopic stabilised mounts looking through two of the landing lights in the centre of the camera deck. Optics would direct the camera angle to the correct flight paths one for jet aircraft and one for slower piston aircraft. The optics would include crosswires to show whether the approaching aircraft was on the correct path in the centre of the crosswires. The cameras would capture any last-minute wing adjustment, a principle cause of crashes. A further camera installed on the superstructure would cover the landing to the point the aircraft stopped, and the pilot emerged. The pilot would then walk to the control room and see his landing in considerable detail with not just the aircraft identity but the pilot himself getting out of the aircraft and walking to the debrief. The video was ready for replay when he arrived in the viewing room.

The system was given the US Navy name PLAT, Pilot Landing Aid Television. The US Navy team were enthusiastic with this proposal and used an emergency ordering procedure to place a contract for a trial system. The trial system was ready in a few months and delivered to the aircraft carrier USS Ticonderoga in San Diego.

The installation team ran into a problem. The Navy wanted the recording control equipment installed in a room in the middle of the ship and the VTR in those days was the size of a big upright piano and could not go through the watertight doors. No problem! A large African-American sailor arrived with an oxyacetylene torch and cut a hole in the thick steel wall big enough for the VTR to pass through then sealed the wall up again afterwards! Another great example of US Can-Do attitude.

Ticonderoga then put to sea and carried out several weeks of landings. These were a great success, and an order was placed for 23 systems, enough for all the aircraft carriers and 3 more systems for vessels that could be used as carriers in an emergency. Coupled with orders for adequate spare modules and parts this was the largest order Ampex had ever received. The US Navy then owned more Marconi MKIV cameras than CBS, who had recently contracted to replace all their cameras. There were more Marconi cameras in the USA than the total in the rest of the world.

When the cameras started to be delivered from Marconi the wooden crates were undamaged but cameras inside the box often had damage. The Marconi response was to make the boxes stronger and more rigid, but the damage continued. I called in the Ampex shipping people, they looked at the problem and a few hours later returned with a heavy-duty cardboard box saying this will solve the problem! Inside the box was another box which exactly fitted the camera. The inner box was held in place in the larger outer box with a number of blocks of polystyrene. They explained that with rough use the outer box would absorb the shock but the inner box and contents would survive undamaged. When this information was passed back to Marconi it was ridiculed by the packing department, so we put an undamaged camera in the box and sent it back to Marconi. The outer cardboard box arrived damaged in the corners, but the camera was undamaged.

The cardboard box design was adopted, and we had no further damage problems. It also had the benefit of being much cheaper than the wooden crates! It totally changed the operation of the packing dept.

Marketing/Sales was another major difference between the companies. Marconi was geared up to sell to large organisations and responded to customer demand, often with tenders with technical specifications. The sales literature was highly technical – mostly specifications. Products had technical names i.e. Marconi MK IV 4 1/2” Television Camera Channel.

Ampex were selling to several hundred TV stations across the USA who didn’t have large technical departments, and the decision makers were often the owner or general manager. So, we had to produce sales brochures more like consumer products. But the biggest difference was in attitude. Ampex didn’t wait to respond to demand, they also created the demand. They would arrange a visit to a station where their VTRs had not yet been purchased and arrive in the afternoon before the appointment. The team would then set up and monitor the station output all evening. At that time, not just news, but a lot of the programs were performed live from the studio. The next morning discussion with the owner would lead to the costs of overtime for late working which was invariably a sore point with the owner/manager. A costed solution would then be presented showing the savings by producing the programs during the day with just a light crew in

the evening to operate the VTR. Once they had bought the VTR they soon began to use editing facilities and soon needed more VTRs.

Back at Marconi

When I returned to Marconi in 1961, Tom Mayer wanted me to adopt the same role I had performed at Ampex on a worldwide basis. This proved to be a very different task. The Marconi representation in many countries was poor and tended to be based on the historical Marconi communications activities. In many cases our agents had never even visited the TV organisations and hence didn’t know anyone. The Can-Do spirit I found at Ampex did not exist in the rest of the world including within Marconi. A lot more effort was required to achieve even minimal success.

Eastern Europe was potentially a good market for TV equipment. We had no representation in any of these countries but Marconi had an employee, Bernard Kane, based in Vienna, who was acting as our representative in all of them. So, Bernard and I organised a 3-month tour behind the Iron Curtain, as it was known at the time. I decided to take a TV Outside Broadcast vehicle operated by TDU the demonstration unit. We kept the numbers down to Dai Evans the driver, and David Smith who could share some of the driving with Dai. David and I would set up the 4-camera unit. We had a demanding schedule and Bernard booked hotels and contacted the TV organisations; all were very keen to receive our demonstration.

Border crossing with the TV vehicle was a significant task, several had already crossed between the UK and Vienna, where we met up with Bernard and his wife Poldi. We set out for the Austrian/Hungary border with Bernard, Poldi and me travelling ahead in Bernards Jaguar. It seemed odd to have Bernards wife with us, but she turned out to be a vital part of our team. Poldi had a gift with languages. She had mastered all the different languages of the countries we visited, could translate for us when needed, but also was able to tell us what was being said when the customers chose to talk among themselves. She was also able to get repairs for Dai when he broke his false teeth on two occasions!!

|

| MK III 1954 |

In each city we would set up the 4 cameras in their studios and let the local engineers operate all the equipment. In every case our equipment was far superior to their existing equipment, but serious negotiation of future sales would have to be by return visits later.

It seems odd today when there are a multitude of instant communication options but as Bernard had warned, from the day we crossed into Hungary we had no contact with the UK until we were safely back in Vienna 3 months later. Telephone calls had to be booked several days ahead in each city, but we left before a connection could be made. I wrote a brief report on each demonstration and posted it back to Marconi together with letters to our wives. Some of these were intercepted en-route and some arrived after we returned to the UK. We had no contact whatsoever from UK.

Sometime later, after we had provided quotations to the various countries within Yugoslavia, I was invited back to negotiate some contracts. A hotel had been booked by the customer and a room prepared to hold the negotiation with 5 of the 6 Yugoslav countries who had decided to place orders with us. Although they were all completely separate contracts they had decided to negotiate together. I found myself sitting at a long table with some 16 negotiators for the 5 buyers. It was clear that any concession made to one would immediately be claimed by all the others. Whenever we reached a sticking point, a tray of slivovitz (Yugoslav plum brandy) would arrive, someone would make a toast, and the slivovitz had to downed in one gulp! It was a very demanding situation!

Exhibitions

With a product like a TV camera, at exhibitions we had to set up a complete operating studio. This took a lot of effort to be ready in the time available. At one exhibition in Montreux, a young sales engineer, let’s call him Mike, arrived to help just when the work had been completed. He joined in for some drinks and quickly became intoxicated. He had not even checked into a hotel, so we allocated him one of the rooms in the Montreux Palace, and a few of the team helped him to the room and got him into bed. The Montreux Palace was a very old hotel and had a free-standing wardrobe adjacent to the door. The wardrobe was moved to hide the door and the team exited via the balcony to the balcony of the next room which we had also booked. The next morning Mike woke up with a hangover and couldn’t find a way out of his room. You can all guess the rest of this story.

After a few exciting and challenging years as Chief Engineer of ITN, designing and building their first colour TV station. I returned to Marconi as Manager of Broadcasting Division. I am not including any stories from that period. Marconi was part of English Electric, who had been taken over by GEC and, in my opinion, it was a disaster for the Marconi Company and all the employees.